Tools and Timbers

31.10.20

Tools & Timbers

Q: How do you decide the sorts of tools to use for different woods?

Do you adjust them according to what wood you are carving?

Putting aside problems common to all species of woods, the awkwardness or lie of the grain, knots and so on, what can make the need for a physical alteration in a carving tool is the wood density: the ratio of fibre mass to air, plus any hard chemical content. Density changes within the annual rings, with age, with the speed of growth, or just between species.

So there are open-grained woods that are, literally, soft and delicate, and tight-grained woods that are very hard. And, of course, a range in between.

How does this affect your tools?

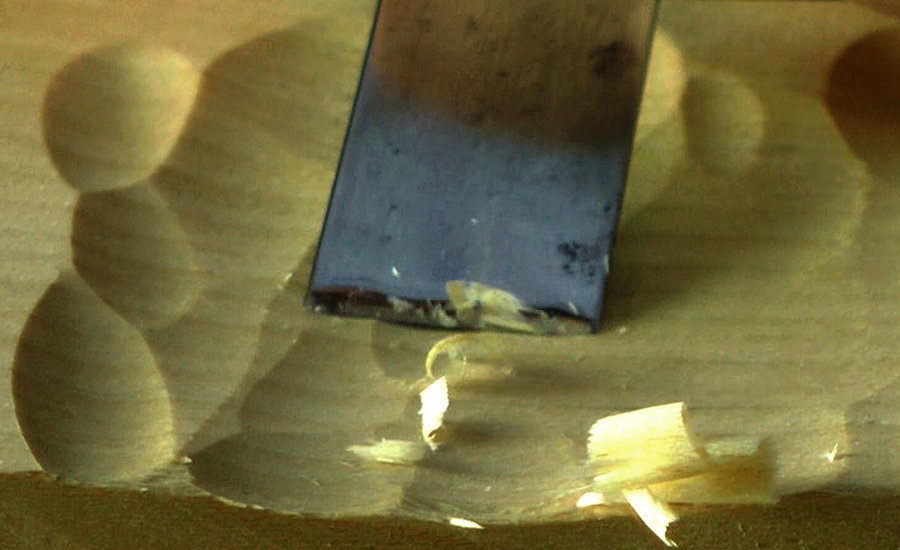

Think about your carving tool: it really is nothing more than a glorified wedge of metal with a 'sharp end' that results from the blade tapering with its bevel(s).

Now, any 'wedge' can be long, thin and fragile or short, fat and tough, and that's no different from your carving tool. A long, keen wedge will cut soft woods like pine readily but collapse when offered to hard wood like oak. Conversely, a shorter, tougher bevel can be malletted though hard wood but will tear up a softer one like a hacksaw.

And there lies the issue: matching wedge to wood.

So, if your wood is too hard for your ‘wedge’ of metal, the cutting edge will crumble, leaving a rough or torn cut. On the other hand if the wood is too soft for your bevel angle, the fibres

will bend and crumble before they are cut, leaving a similarly torn wood surface.

Carvers in the traditional European manner like myself who work side-step this problem by sticking to a narrow range of medium-dense woods: Lime, Mahogany or air-dried Oak for example. We know what works. Step outside that range and we may need a different profile to our gouges.

It's all about the bevel...

I advocate 2 bevels on my carving tools: an outside bevel around 15-20° and an inside bevel around 5-10°. Thus the overall bevel angle—the wedge of metal—will vary between 15-30°, which gives a good balance between a tough cutting edge and one that requires the least effort. There's a whole sharpening section on Woodcarving Workshops.tv where you can find out more.

If I were cutting a much softer, less dense wood (eg. pine), I would:

- Re-set the outer bevel to a more acute cutting angle (more like 15° or less).

- Decrease the overall bevel angle by lengthening the inside bevel, or even leaving it out.

If I were cutting a much harder, denser wood (eg. box), I would

- 1. Re-set the outer bevel to a slightly greater angle (20-25°) and re-sharpen.

- 2. Increase the overall bevel angle by adding more inside bevel. The inner bevel acts as a buttress, throwing the cutting edge more into the centre of the blade.

In both cases I'm playing with that wedge. Some carvers are happy carving with a single outside bevel, but the wedge principle is the same.

In the past, trade carvers working in timber of greatly differing densities (hard oak to soft pine for example) would have some of their tools duplicated, set and sharpened accordingly to save time, at least their favourites.

Whether or not it's worth you doing this yourself will depend on the varieties (densities) of woods in which you choose to work.

Related videos:

Do check out these workshops that fill out what I'm saying here: