What Makes the Corner of a Gouge Break?

16.08.22

I like to keep an acute bevel angle on my tools, and I like tools with the hardest steel. However, sometimes these hard blades fail and great chunks break off the cutting edge, which means a major regrind! What am I missing?

Reading time: 2 mins

Yes, that really hurts!

Several things to think about here but, first, let's just talk about the tempering of your tools.

Tempering - heat treatment - is what gives the steel its balance between hardness and resilience: A harder steel gives a longer-lasting edge but is more brittle and thus easier to break the metal. Softer steel is more resilient.

(The degree hardness of hardness also varies along the blade with harder steel towards the cutting end and somewhat softer, more resilient metal towards the shoulder - to resist the stress of mallet work, say, or the scooping action of a shortbent gouge).

Myself, I also prefer carving tools with a harder temper such as Henry Taylor or Stubai, and some older Herring and Addis tools. On the other hand, to my sensibilities, Ashley Iles tools are on the softer end of the spectrum, with Auriou and Pfeil mid-range. I'm not being scientific here, just my sense of them and not all carvers would arrange different makes in the same way along a hard-soft spectrum. It’s also really important to remember that there are other qualities to the tools you buy such as the shape of curves and sweeps or the thickness of the blade. All very personal matters.

So, bottom line, there isn't really a problem with using a gouge with a harder temper as such.

My experience of whether the edges of blades crack and how long they retain their edges depends significantly on 2 things: technique and bevel angle. If you crack the edge or corner off a carving tool, then almost certainly the problem is lying here:

1. Technique

If you combine good carving practices with the harder steel, the edges will last longest of all. This is the strategy of the professional carvers I know—if only because we can't afford the time to regrind!

So:

- Don’t lever the blade when the edge is embedded in the wood. AKA the 'Crowbar School of Woodcarving’.

- Keep the blade moving forwards through the wood as you scoop the facet.

- Don’t lower the handle suddenly or prise the wood.

2. Bevel Angle

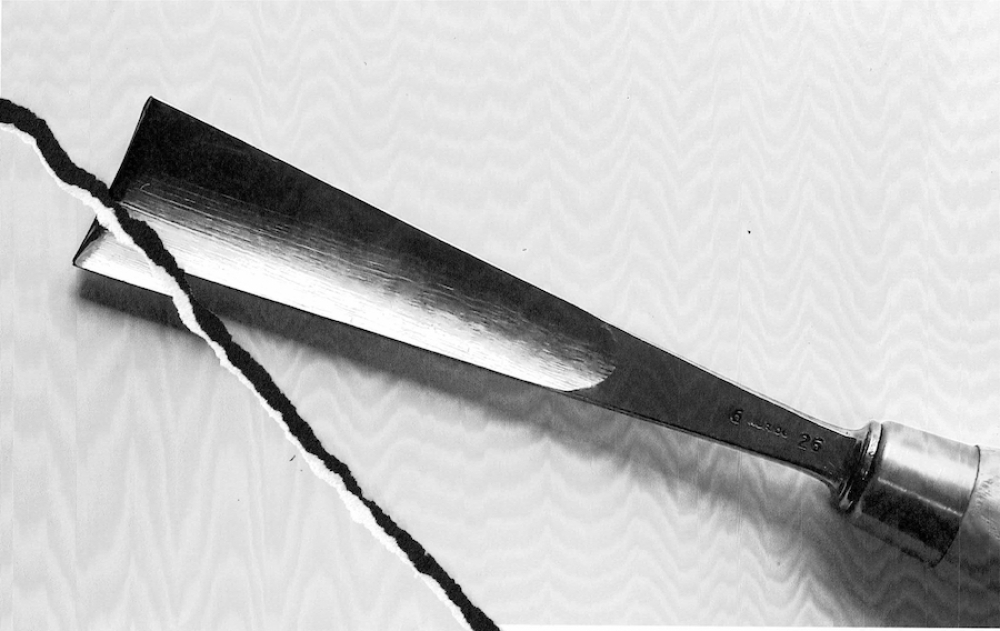

The cutting edge is the tip of a wedge of metal. Yes?

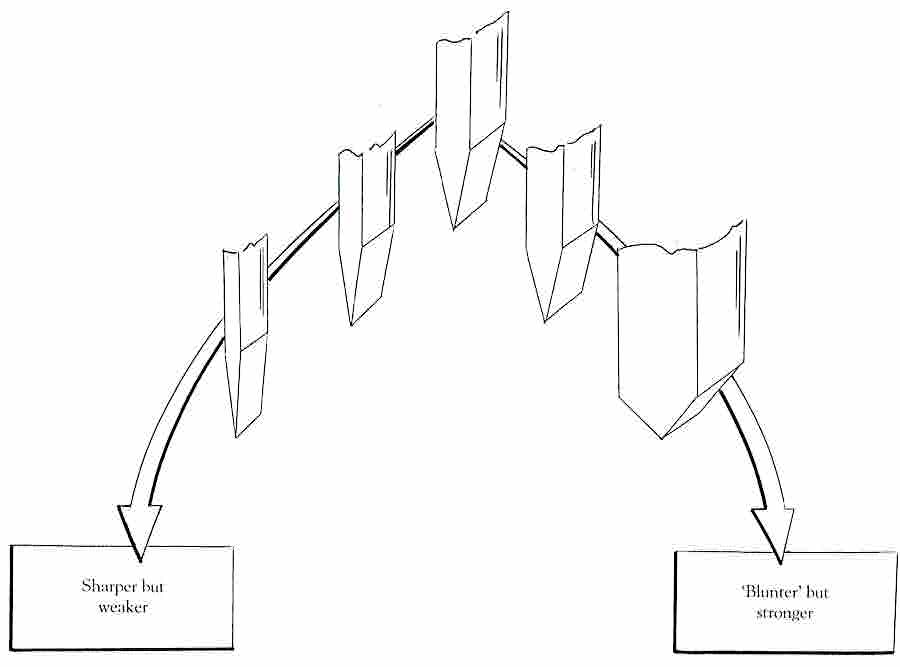

The 'wedge' results from the angle of the bevels, inner and outer. You are balancing (1) acuteness of wedge and ease of cut, but more fragile, with (2) a wider wedge angle, giving a tougher edge but needing more work to push the tool through the wood.

So not all tools need the same bevel angle. For example: tools subject to heavy forces—mallets—need tougher, less acute, bevels.

The secret to a thin but tough edge, whatever the tempering, is the inner bevel.

With a desire for an acute angle, the inner bevel comes into it’s own, buttressing the longer outer bevel with a shorter one, toughening it while keeping the amount of metal you are trying to push through the wood to a minimum.

More on the inside bevel in the recommendations below.

Related Videos: